DBMS architecture is rarely captured in a single blueprint; every engine still has to choose hardware trade-offs, communication tools, and storage patterns to match its goals. This article follows the common layers-transport, query processing, execution, storage engines, and the memory hierarchy-to help you internalize the keyword “DBMS architecture” and see how each layer keeps data flowing. Use this baseline before diving into Relational Data Modeling, Relational Normalization, or SQL Index Performance.

Understanding DBMS architecture#

Few systems match this stack exactly, yet most databases expose similar layers so you can reason about how data moves from clients down to disks. This overview highlights the usual responsibilities so that vendor diagrams become readable maps rather than mysterious flowcharts.

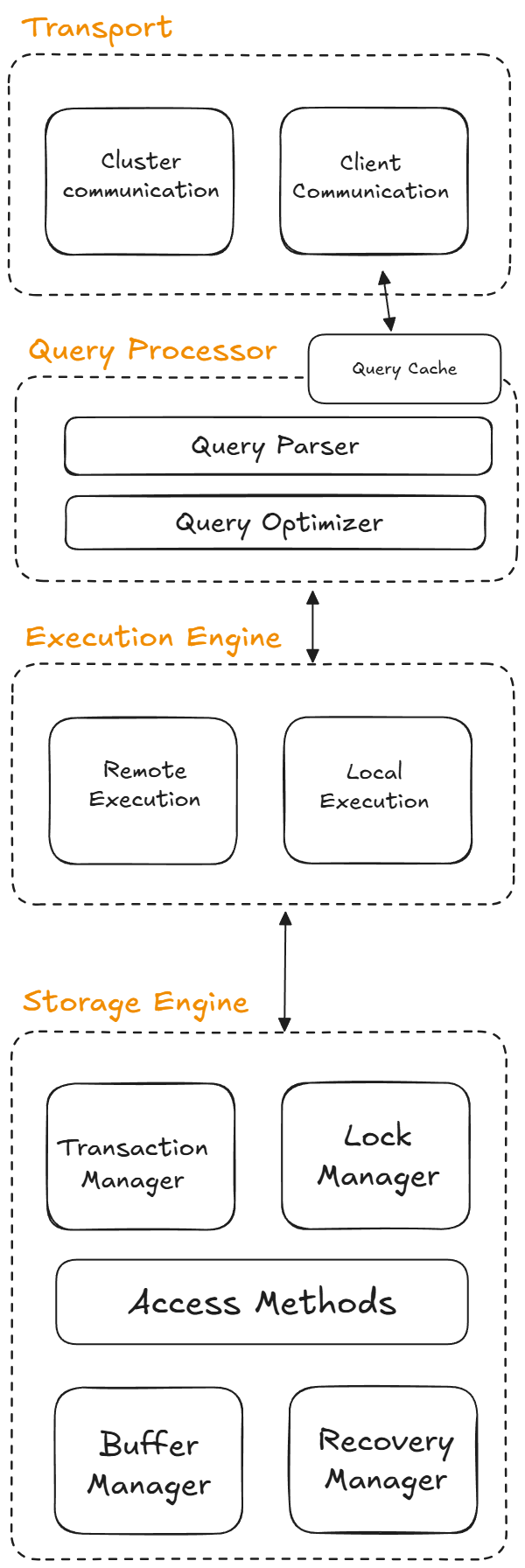

Transport layer#

The transport subsystem receives SQL or DSL requests through the client communication component and then hands the statement to the rest of the engine. It also brokers inter-cluster communication so distributed replicas, coordinators, and proxies can operate transparently.

Query processor#

Once the transport layer delivers the request, the query processor parses and validates the statement while enforcing permissions. The optimizer rewrites the query tree, removes redundancies, and picks the cheapest execution plan; you can inspect its rationale with EXPLAIN. Many processors also keep a cache so identical requests can return cached results instead of repeating work.

Execution engine#

The execution engine runs the plan produced by the optimizer, coordinating operators such as scans, joins, and aggregations. Remote execution nodes read from partitioned peers when data is stretched across machines, while local execution relies on the storage engine to satisfy reads and writes.

Storage engine overview#

The storage engine is where data landing, indexing, and recovery happen; it decides how bytes end up on disk and in RAM. This component largely determines the database family (row store, column store, log-structured, etc.) and its physical layout, organizing data according to the chosen model so that access patterns can stay efficient.

Storage engine internals#

The storage engine relies on several subcomponents: the Transaction Manager schedules transactions and enforces logical consistency, the Lock Manager handles concurrent updates, Access Methods maintain the physical structures (heaps, B-trees, and similar), the Buffer Manager caches pages in RAM, and the Recovery Manager tracks write-ahead logs to rebuild the system after a crash.

Storage engine choices#

Some systems expose multiple engines (for example, SQLite offers both memory and disk engines) so you can pick the right trade-off. There are two broad philosophies for disk layouts: page-oriented engines write fixed-size pages, while log-structured engines append changes and reconcile them later; the latter shines for heavy writes, while the former works better for balanced workloads with frequent reads.

Memory management#

Memory planning and data organization are critical to DBMS efficiency, especially for disk-based architectures that treat the disk as the persistence layer. Systems tune caches, readahead, and eviction policies to balance speed, hardware resources, and the cost of disk I/O, while the engine ensures data buffered in RAM eventually lands safely on disk.

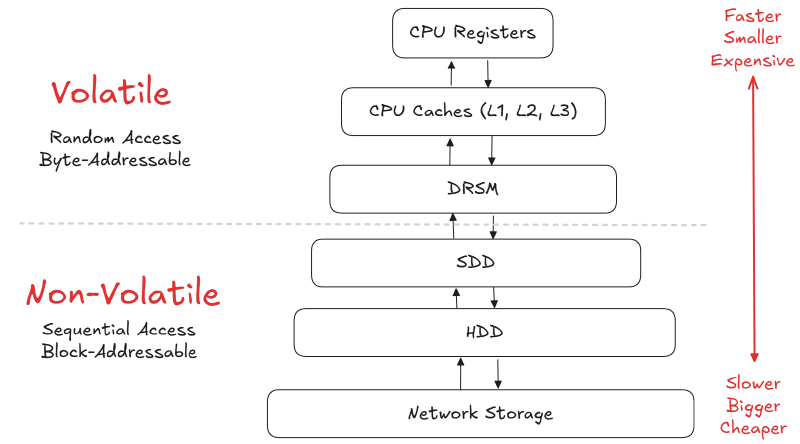

Memory hierarchy#

Understanding where data sits in the memory pyramid helps you choose the right algorithms when the DBMS migrates pages between layers.

| Level | Memory type | Latency | Capacity | Cost per bit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU registers | On-CPU internal memory | ~1 cycle | Few KB | Extremely high |

| CPU cache (L1-L3) | Fast volatile cache | 1-4 ns | Hundreds of KB to a few MB | High |

| RAM (main memory) | Volatile main memory | ~100 ns | GB | Moderate |

| SSD/NVMe | Mass storage (flash) | ~16,000 ns | Hundreds of GB to TB | Low |

| HDD (hard disk) | Mass storage (spinning) | ~2,000,000 ns | Terabytes | Very low |

| Distributed FS | Network-attached pools | ~50,000,000 ns | Petabytes | Very low |

Sequential vs random access#

Random access on persistent media is almost always slower than sequential scans, so engines cluster writes and reads into contiguous blocks; MySQL, for instance, writes sequentially to a buffer before a background process redistributes pages. Allocating multiple contiguous pages at once is called an extent, and the goal is to stay ahead of datasets larger than RAM without triggering frequent disk sweeps, because each expensive disk operation favors sequential access over scattered reads.

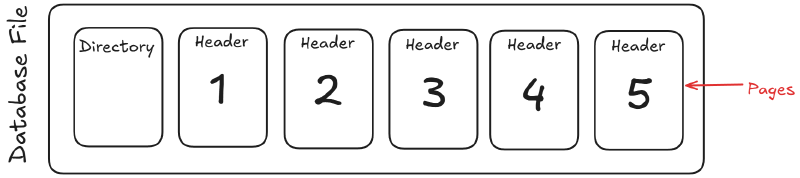

Database storage#

The storage engine keeps the database files, organizing them as collections of pages while tracking which regions are free. Most DBMSes rely on external replication for redundancy rather than duplicating pages on disk. A page is a fixed-size block that keeps similar data together and carries a pageID scoped to the engine instance, the database, or the table. A redirection layer maps those IDs to physical offsets, and typical page types include hardware pages (often 4 KB, ensuring atomic writes), OS pages (4 KB with possible huge-page extensions), and database pages (512 B-32 KB). Read-heavy workloads often prefer larger database pages for throughput.

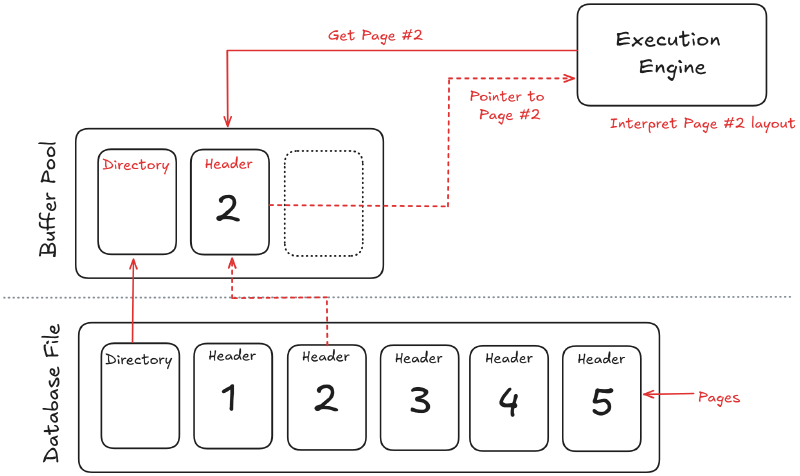

Disk-oriented DBMS storage#

The database lives as one or more files on disk, where directories keep metadata about the file contents and each file splits into fixed-size pages so the engine can jump between offsets quickly.

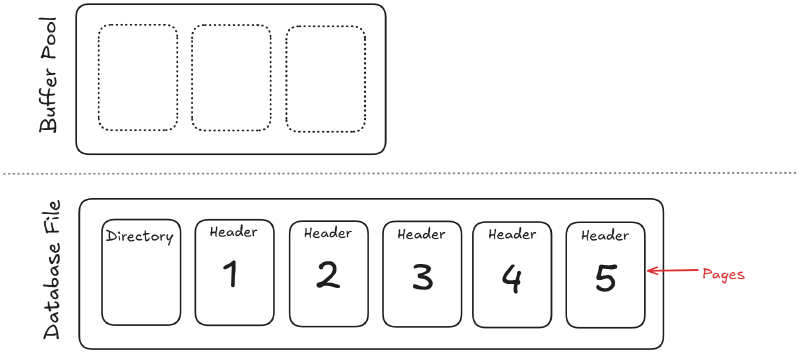

Buffer cache and RAM#

Above the disk is the buffer cache in RAM; pages promoted from disk land there so the execution engine can access them quickly.

Execution engine in action#

The execution engine turns the optimized plan into work by scanning pages, joining rows, and streaming partial results.

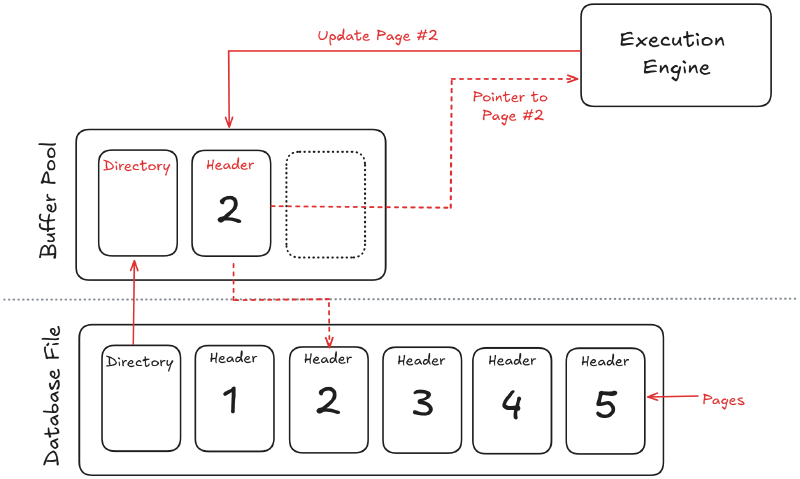

Updates and writes#

Writes follow the same path as reads: the execution engine updates buffered pages, logs the change, and eventually flushes to disk.

Key challenges#

Two problems always surface: how the DBMS represents databases as files on disk and how it moves data between memory tiers. Most DBMSes use proprietary file formats, so you cannot import a data file from one engine directly into another. Early systems in the 1980s relied on proprietary filesystems, and a few enterprise-class engines still support those for maximum control and predictability.

These challenges recur in the modeling and indexing lessons, so frame every future tweak with the same question: “How does this affect storage layouts and memory movement?”